Magnetron Sputtering Rotating Cylindrical Target High Voltage Contact System

Rotating cylindrical magnetron targets are a cornerstone of high-throughput, industrial-scale coating processes, particularly in architectural glass, display, and web coating applications. Their primary advantage is high material utilization, often exceeding 80%, compared to less than 50% for planar targets, as the erosion groove is continuously moved across the target surface. However, the implementation of a rotating cathode introduces a significant engineering challenge: how to reliably deliver high electrical power—often hundreds of kilowatts at voltages of 300-600 VDC or in pulsed DC mode—to a constantly moving, water-cooled cylinder inside a high-vacuum chamber. The high-voltage contact system, or "rotary feedthrough," is the critical, often under-specified, component that solves this problem. Its design and performance directly dictate process stability, target life, arc frequency, and overall system uptime.

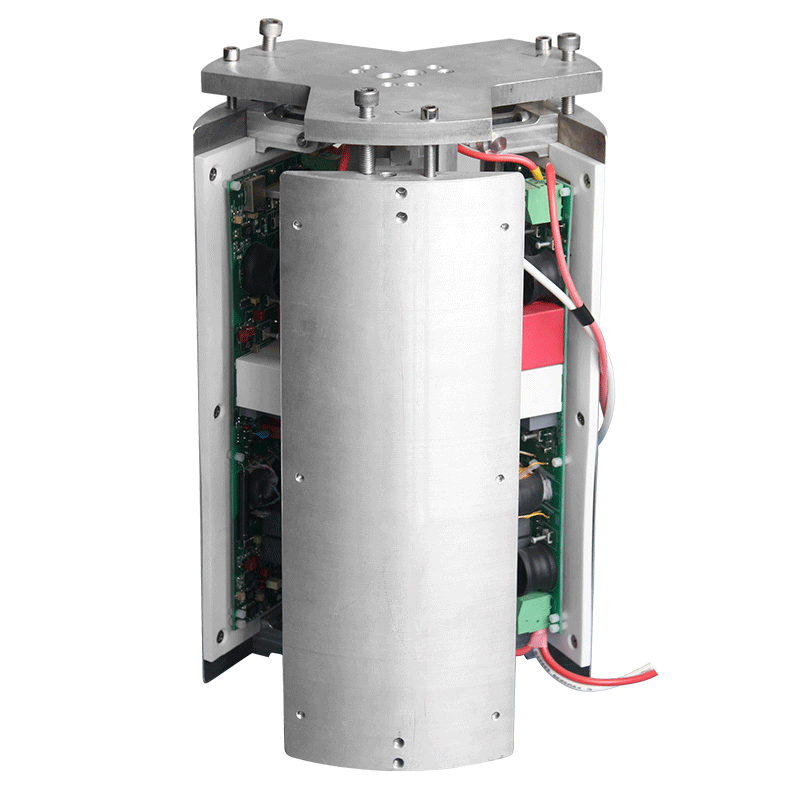

The core function of the contact system is to provide a low-resistance, stable electrical connection between the stationary power supply output and the rotating target tube. This must be accomplished while maintaining the vacuum integrity of the chamber and accommodating the flow of high-volume cooling water to the target's interior. A typical system employs a multi-faceted approach. The primary electrical connection is often made via a set of high-current, low-voltage-drop sliding contacts, commonly made of copper-graphite or silver-graphite alloys. These "brushes" or "shoes" are spring-loaded against a polished, hardened copper slip ring that is mechanically connected to the target tube. The design must ensure uniform pressure and contact area across all brushes to distribute the enormous current (which can exceed 1000 A for large systems) and minimize localized heating. The contact material is chosen for a balance of low electrical resistance, good thermal conductivity, low wear rate, and resistance to welding or sticking under high current.

However, the high-voltage aspect is not about kilovolts of potential in the traditional sense (the cathode potential is typically -300 to -600V relative to ground), but about managing the high *power* and the hostile plasma environment. The contact resistance must be extremely low and, more importantly, stable. Any variation in contact resistance, due to vibration, wear, or arcing, manifests as a change in the voltage drop across the contact system. Since the magnetron power supply regulates voltage or power based on its own output terminals, an unstable contact resistance means the actual voltage applied to the plasma is fluctuating. This leads to process drift, changes in deposition rate, and can precipitate arc events as the operating point on the magnetron's voltage-current characteristic curve shifts unpredictably. Therefore, the contact system is designed not just for initial low resistance, but for maintaining that performance over thousands of hours of rotation. This involves robust mechanical design to minimize vibration, effective dust shielding to prevent sputtered material from contaminating the contact surfaces, and sometimes active cooling of the slip ring.

The integration with cooling is paramount. The target tube itself is water-cooled from the inside. The rotary union that delivers this water is typically concentric with the electrical slip ring assembly. This creates a complex mechanical assembly where high-pressure water and high electrical current are in close proximity. Electrical isolation and prevention of galvanic corrosion are critical design considerations. The entire assembly must be electrically isolated from the chamber ground except through the intended path. Leakage currents through cooling water, which can become slightly conductive, must be managed with insulating sections in the water path and careful grounding schemes.

For pulsed DC magnetron sputtering (used for reactive deposition of dielectrics), the demands on the contact system intensify. The power supply switches polarity at frequencies of tens to hundreds of kilohertz. The contact system must have low inductance to allow these fast current transitions without generating large voltage spikes (V = L di/dt). A high-inductance connection would limit the achievable pulse rise time and efficiency, and could cause voltage overshoots that trigger arcs. Therefore, the brush and slip ring geometry is designed to minimize loop area, often using coaxial or paired-return configurations. The brush material must also handle the micro-arcs that can occur during polarity reversal without excessive pitting or degradation.

Monitoring and diagnostics are built into advanced systems. The voltage drop across the contact assembly can be measured using dedicated sense leads. An increasing trend in this voltage drop indicates brush wear or contamination, enabling predictive maintenance before process stability is affected. Temperature sensors on the slip ring can detect abnormal heating due to increased resistance or cooling failure. This data is fed back to the power supply controller or a supervisory system, which can alarm or even initiate a controlled shutdown.

In hostile reactive environments (e.g., depositing oxides or nitrides), the contact system is vulnerable to the ingress of reaction products. A dedicated purge system using an inert gas (like argon or nitrogen) is often employed to create a positive pressure barrier around the slip ring and brush assembly, preventing conductive oxide dust from settling on the contacts and causing short circuits or increased resistance.

In summary, the high-voltage contact system for a rotating cylindrical magnetron is a masterpiece of applied electro-mechanical engineering for harsh environments. It is the vital, dynamic link that translates the stable output of a high-power supply into stable power delivered to a moving plasma. Its success hinges on achieving and maintaining near-zero and stable contact resistance, managing immense thermal loads, accommodating fast current transients for pulsed power, and resisting the degrading effects of vacuum, vibration, and chemical contamination. The reliability of the entire high-throughput coating line often depends on the unsung performance of this rotary interface.