High-Voltage Synchronization for Excimer Laser Beam Scanning

Excimer lasers, producing high-energy pulses of ultraviolet light, are indispensable tools in micromachining, semiconductor lithography, and medical applications like refractive eye surgery. In processes requiring patterning or selective material removal, the laser beam must be scanned across the workpiece with high precision and speed. This is commonly achieved using galvanometer-based scanners with mirrors or, for the most demanding applications, acousto-optic or electro-optic deflectors. The synchronization between the high-voltage pulses driving the laser discharge and the high-voltage or high-current signals controlling the beam positioning system is critical. Any temporal misalignment or jitter can result in blurred features, positional inaccuracies, and inconsistent process results, particularly when dealing with pulse durations in the nanosecond regime.

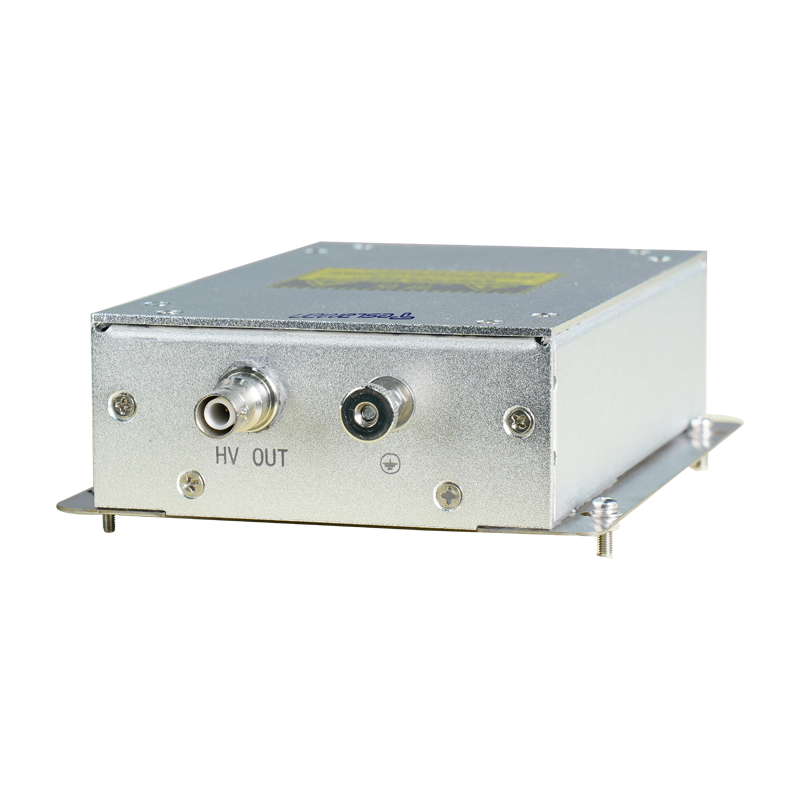

The excimer laser itself operates by applying a very fast, high-voltage pulse across a gas-filled chamber, typically using a thyratron or a solid-state pulsed power switch. This pulse, which can exceed 30 kV with rise times under 100 nanoseconds, initiates a dielectric breakdown and population inversion in the gas mixture. The optical pulse follows shortly after. For scanning applications, the timing of this electrical pulse must be locked to the beam positioning system's clock. The scanner, whether a galvo or an electro-optic cell, requires a command signal to move the beam to a specific coordinate. The laser must fire exactly when the beam is stationary and correctly positioned. If the laser fires during the scanner's movement, the energy will be deposited along a smear, ruining the feature.

Therefore, a master timing generator, often with sub-nanosecond jitter specifications, is employed. This generator produces two primary synchronized outputs. The first output triggers the high-voltage pulser for the laser discharge. The second output, which may be advanced or delayed by a precisely calibrated interval, commands the beam scanner to its target position. This interval must account for the electromechanical or electronic response time of the scanner. For a galvanometer, this includes the time for the drive amplifier to slew the motor to the new angle and for the mirror to settle. For an electro-optic deflector, the response is nearly instantaneous, but the high-voltage driver for the crystal must still settle. The synchronization system must inject the correct delay so that the laser pulse arrival at the workpiece coincides perfectly with the moment the beam position is stable and correct.

This becomes exponentially more complex in vector scanning or polygon scanning modes, where the laser fires at irregular intervals as it traces a path. Here, the scanner controller provides a ready signal for each firing position. The laser's high-voltage pulser must then fire on-demand with ultra-low latency upon receiving this signal. This requires a pulsed power supply capable of operating in an externally triggered, burst-mode with minimal and consistent trigger-to-light delay. Any variation in this delay from pulse to pulse (jitter) will cause positional errors.

Furthermore, the high-voltage environment of the laser can induce electromagnetic interference (EMI) that corrupts the low-voltage logic signals of the scanner controller. Robust system design is necessary, involving optical isolation of all timing and trigger lines, separate grounded enclosures for the laser high-voltage modules and the scanner electronics, and meticulous attention to cabling and shielding. In some high-power systems, the laser pulse energy may need to be modulated from shot to shot (e.g., for depth control in ablation). This requires an additional layer of synchronization where a fast high-voltage amplitude control circuit receives its setpoint from the master controller in sync with the positioning command.

Achieving this high level of temporal coordination transforms the excimer laser from a mere light source into a precision machining tool. It enables the fabrication of diffractive optical elements with sub-micron features, the precise cutting of polymer stents for medical devices, and the production of intricate patterns in thin films without thermal damage to surrounding areas. The reliability of the entire process hinges on the nanosecond-level precision of the high-voltage synchronization scheme, making it a cornerstone technology for advanced laser material processing.