Excimer Laser Pulse Energy Closed-Loop Power Supply

Excimer lasers, producing high-power pulses of ultraviolet light, are indispensable tools for semiconductor lithography (DUV), precision micromachining, and medical applications. The critical process parameter in most of these applications is the pulse energy, as it directly affects exposure dose, ablation depth, or treatment efficacy. Fluctuations in pulse energy, caused by gas chemistry changes, discharge instability, or optic degradation, lead to process variation and yield loss. Therefore, maintaining constant pulse energy from shot to shot is paramount. This is achieved through a closed-loop control system where the high-voltage power supply charging the laser's main storage capacitor is dynamically adjusted based on real-time measurements of the output pulse energy. The design and performance of this high-voltage charging supply are fundamental to the stability and control bandwidth of the entire laser system.

The core of an excimer laser is a pulsed gas discharge. Electrical energy is stored in a capacitor bank (the "storage capacitor") and then rapidly switched via a thyratron or solid-state switch into the gas-filled laser chamber. The voltage to which this capacitor is charged, V_charge, determines the stored energy (E = 1/2 * C * V_charge^2). This energy, minus losses, is converted into light. Thus, controlling V_charge is the primary method for regulating output pulse energy. A closed-loop system works as follows: a beam splitter directs a small fraction of each laser pulse to an energy monitor (photodiode or pyroelectric detector). The measured energy of pulse *n* is compared to a user-set target energy. The error signal is processed by a control algorithm, which calculates a new charging voltage setpoint for pulse *n+1*. The high-voltage power supply must then charge the storage capacitor to this new voltage before the next trigger command arrives.

This deceptively simple feedback loop places extreme demands on the high-voltage charging supply. The first requirement is exceptional voltage setting resolution and accuracy. To achieve precise energy control, often with stability specs of ±0.5% or better, the supply must be capable of adjusting its output voltage in fine steps. For a typical 1-2 kJ excimer laser charging to 20-40 kV, this may require resolution on the order of 1-10 volts. More importantly, the actual output voltage must match the commanded setpoint with high accuracy and low drift. This necessitates a precision internal voltage reference and a feedback loop that measures its own output via a high-accuracy, high-voltage resistive divider.

The second, and most critical, requirement is speed and reproducibility. The time between consecutive laser pulses—the pulse repetition frequency (PRF)—can range from single-shot to several kilohertz. The power supply has only the inter-pulse period to complete its task. Its operation involves two phases: first, it must very quickly discharge any residual voltage on the capacitor (a "dump" function often handled by a separate circuit) to a baseline; second, it must charge the capacitor to the new setpoint voltage. The charging supply is typically a resonant or switching converter. The charging time must be consistent and predictable. Any jitter in the charging time or the final voltage settling time would prevent the laser from firing at the precise moment required, or cause it to fire before the capacitor has reached the correct voltage. For high-PRF lasers, the charging window is extremely short, demanding supplies with very high power density and efficient, fast charging topologies like series-resonant converters.

The control loop's dynamics are crucial. The laser's energy response to a change in charging voltage is not perfectly linear and can vary with gas age, optic contamination, and temperature. A sophisticated controller, often a digital signal processor (DSP), implements an algorithm that may be adaptive, learning the laser's current gain (energy/voltage^2) and adjusting its corrections accordingly. The power supply must interface seamlessly with this digital controller, accepting setpoint commands via a fast digital interface (e.g., serial, Ethernet) or an analog input with high bandwidth. The supply's own internal response to a setpoint change must be fast and well-damped. If the supply's internal control loop is slow or oscillatory, it will destabilize the outer laser energy control loop.

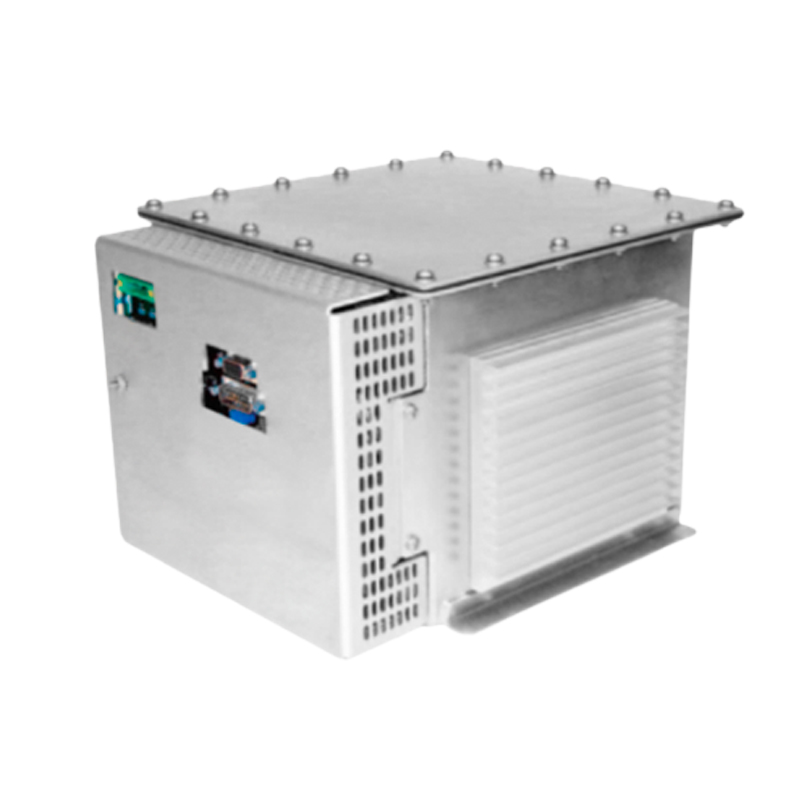

Furthermore, the operational environment is electrically hostile. The discharge of the capacitor bank through the thyratron creates enormous current spikes and electromagnetic interference (EMI). The high-voltage charging supply must be impeccably shielded and filtered to prevent this noise from corrupting its own sensitive control electronics or the energy monitor's signal. Its grounding scheme must be carefully designed to avoid ground loops that inject noise. The supply must also be inherently protected against internal arcs and external flashover, which are not uncommon in high-power pulsed laser systems.

Reliability over millions of pulses is another key design goal. The charging supply operates in a continuous cycle of high-voltage stress. Components like high-voltage capacitors, diodes, and transformers are subject to significant thermal and electrical cycling. Robust design, conservative derating, and effective cooling are essential. The supply often includes comprehensive self-diagnostic and fault-reporting features, communicating status to the laser's main control system to facilitate predictive maintenance.

In essence, the closed-loop high-voltage charging supply for an excimer laser is a high-speed, precision instrument embedded in a high-noise industrial environment. Its performance is measured by its voltage setpoint accuracy, its charging speed and repeatability, its immunity to EMI, and the stability of its response over the laser's operational lifetime. By providing the fast, accurate, and stable voltage adjustments demanded by the energy control algorithm, this power supply is the critical actuator that transforms a naturally fluctuating gas discharge into a stable, process-qualified light source, enabling the nanometer-scale precision of modern lithography and the repeatability of industrial micromachining.