Electron Beam Melting Process Recoil Electron Suppression Power Supply

Electron beam melting (EBM) and welding are high-energy density processes where a focused beam of high-energy electrons transforms metallic powders or solid workpieces. A significant but often overlooked phenomenon in these systems is the emission of recoil or backscattered electrons. When the primary high-energy beam (typically 30-150 keV) strikes the metallic target, a substantial fraction of electrons, possessing significant kinetic energy, are scattered back out of the target. These recoil electrons can cause several detrimental effects: they can overheat and damage sensitive components in the gun column (like the cathode or bias electrodes), generate parasitic X-rays, and create unstable space charge conditions that defocus the primary beam. A dedicated recoil electron suppression power supply is integrated into the gun assembly to actively mitigate this issue, thereby protecting the system and improving process stability.

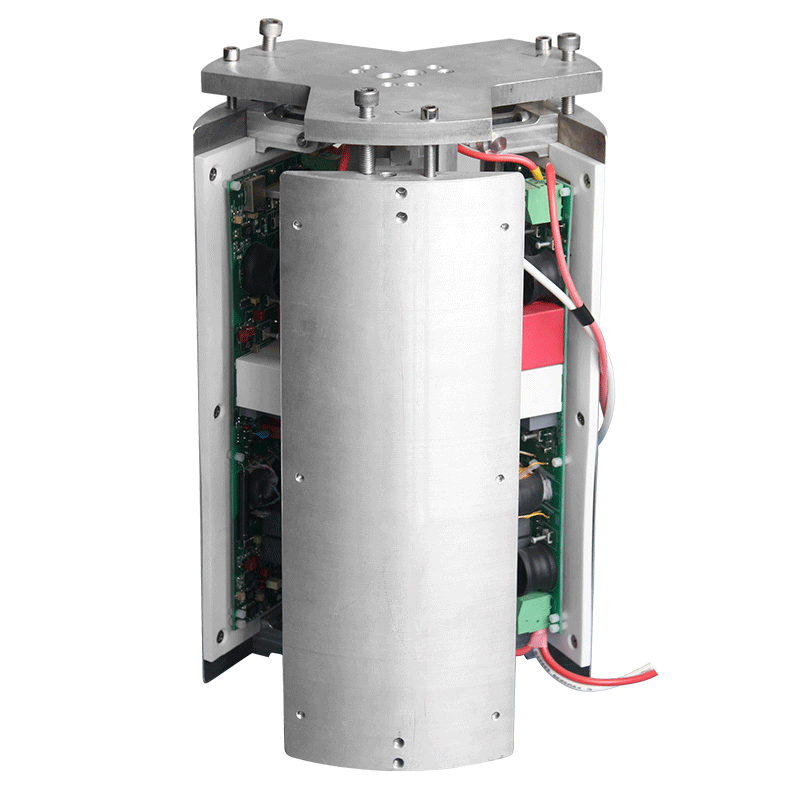

The suppression mechanism is electrostatic. A cylindrical or conical electrode, often referred to as a suppressor or bias electrode, is positioned between the anode and the final focusing lens, coaxial with the beam path. This electrode is biased to a high positive potential relative to the cathode, typically several kilovolts. The electric field created by this electrode forms an electrostatic barrier for low-energy electrons trying to travel back up the column. Primary beam electrons, accelerated by the full cathode-to-anode potential (e.g., -60 kV), have sufficient kinetic energy to pass through this positive barrier on their way down to the workpiece. However, recoil electrons, having lost much of their energy in the scattering process within the target, often have energies of only a few keV or less. As they attempt to travel back up the column, they encounter the strong repelling field from the positively biased suppressor electrode. Their forward motion is halted, and they are deflected radially outward, eventually striking the grounded walls of the gun chamber where their energy is safely dissipated as heat.

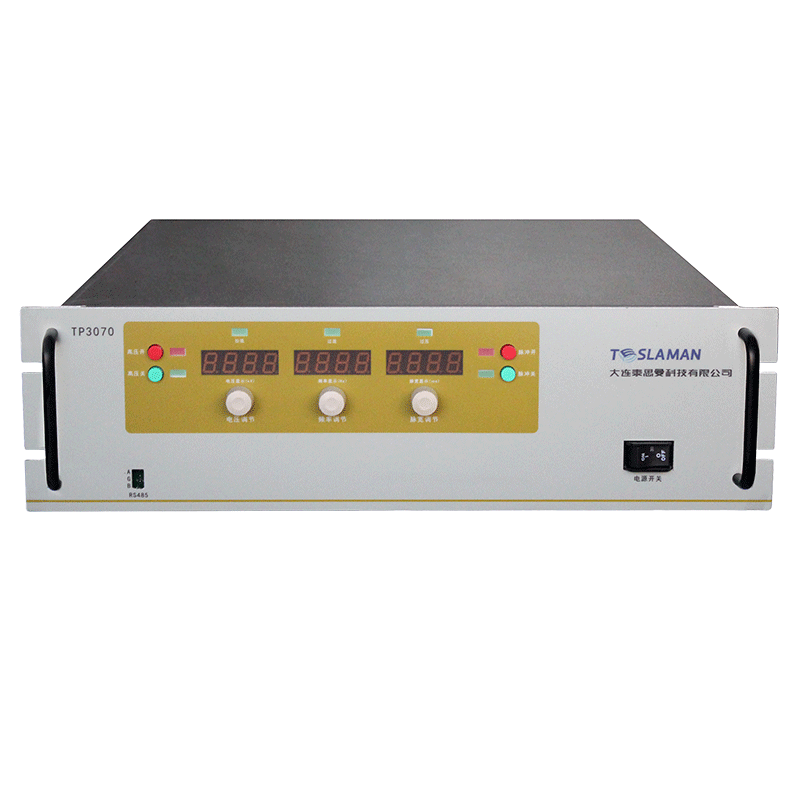

The design of the suppression power supply must account for a harsh and dynamic environment. It must provide a stable positive high voltage (e.g., +2 kV to +15 kV) in close proximity to the main high-voltage cathode potential (e.g., -60 kV). This means the suppressor supply is effectively floating at a potential of approximately -58 kV relative to ground. Therefore, it must be fully isolated. This is achieved through an isolated DC-DC converter topology. A low-voltage input (e.g., 24 VDC) is fed via an isolation transformer to a switching converter that generates the required positive high voltage, all contained within a module that can withstand the full cathode potential. Feedback for voltage regulation is provided by an isolated sensor, such as a fiber-optic transmitter or a dedicated isolation amplifier powered from the floating side.

The load characteristics are non-linear and can vary. The suppressor electrode draws a current composed of intercepted recoil electrons and possibly a small leakage current. During process initiation, when the beam first strikes the workpiece, there can be a surge in recoil electron flux. The supply must be able to source this current without its output voltage sagging, as a drop in the suppression potential would allow more recoil electrons to pass, potentially creating a runaway condition. Thus, the supply is designed with a low output impedance and adequate current headroom. It often includes a fast-response current limit circuit to protect itself if an arc or excessive emission occurs.

Integration with the gun control system is crucial. The suppressor voltage is not a fixed parameter; it may be optimized based on the main accelerating voltage and beam current. A control algorithm may increase the suppression bias proportionally with the main beam energy to ensure effective trapping of the higher-energy recoil electrons that result. Furthermore, the suppressor supply is interlocked with the main high-voltage system. It is typically enabled only after the main beam is established and disabled before the main high voltage is ramped down, ensuring the gun column is always protected during operation. Diagnostics are also important; monitoring the suppressor current can provide indirect information about the process conditions and the level of backscattering, which can be useful for closed-loop control or fault detection. By actively managing the population of stray electrons within the column, the recoil electron suppression power supply enhances the longevity of the thermionic or cathode assembly, reduces parasitic radiation, and contributes to a more stable and predictable primary beam focus, which directly translates to improved melt pool control and part quality in additive manufacturing or precision welding.