Electron Beam Lithography Proximity Effect Real-Time Compensation Power Supply

In electron beam lithography (EBL), the "proximity effect" is a fundamental resolution-limiting phenomenon. When a focused electron beam writes a pattern on a resist-coated substrate, a significant portion of the incident energy is not deposited locally but is scattered laterally within the resist and substrate, exposing areas adjacent to the intended pattern. This leads to linewidth variations, bridging between features, and loss of critical dimension control. While software-based proximity effect correction (PEC) during pattern preparation is standard, its efficacy is limited by simplifications in the physical model and fixed exposure parameters. Real-time compensation takes a more direct approach by dynamically modulating the beam's energy or current density during the write process, based on real-time calculations of local pattern density. This requires a high-voltage power supply for the electron gun accelerator that can modulate its output with extreme precision and speed, acting as the final actuator in a nanoscale feedback loop.

The principle involves varying the incident electron energy to control the penetration depth and scatter volume. A higher accelerating voltage produces a more forward-scattered beam, depositing energy deeper and with a narrower lateral spread, while a lower voltage increases lateral scattering. By strategically lowering the voltage in areas of dense features (where scattered dose from neighboring pixels adds up) and raising it in isolated areas, the net energy deposition profile can be homogenized. This demands a power supply capable of rapid, small-amplitude modulations of the high voltage (e.g., 50-100 kV) with negligible settling time and overshoot. A change of even 500 volts must be executed and stabilized within microseconds as the beam jumps between pixels.

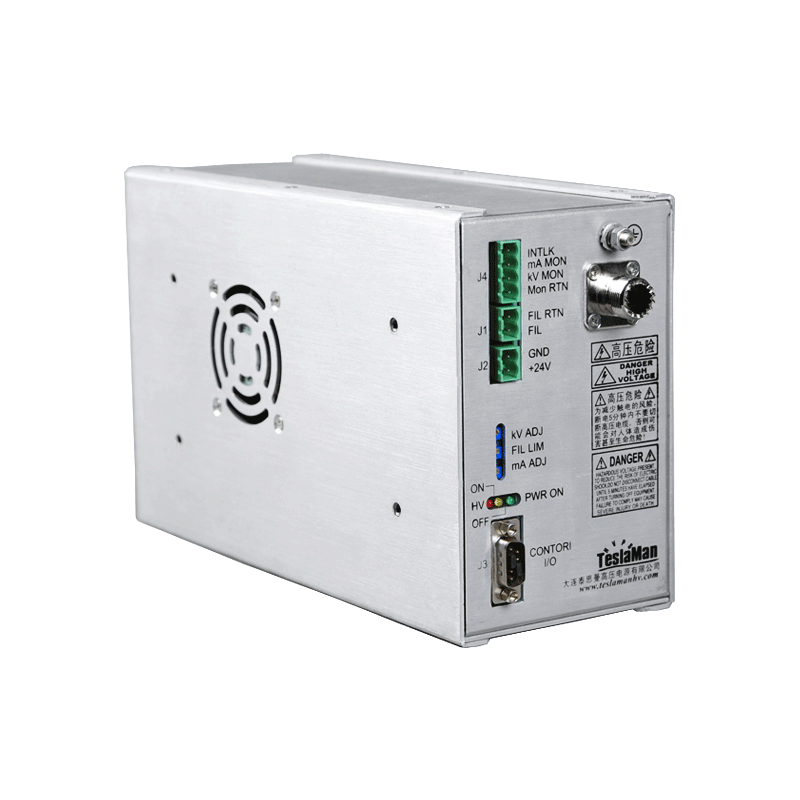

The architecture for such a supply is a departure from the ultra-stable, constant-voltage supplies used in conventional EBL. It is a hybrid amplifier. A highly regulated, low-noise base supply provides the primary high-voltage DC level. In series with its output is a wideband, high-voltage linear amplifier module. This module, receiving an analog modulation signal from the pattern generator's real-time calculator, adds or subtracts a relatively small voltage (e.g., ±1-2 kV) to the base level. Using a linear amplifier, rather than trying to modulate the main switcher, ensures the necessary bandwidth (hundreds of kHz to MHz) and low phase lag. The linear stage itself is powered by a fast, intermediate switching supply. The challenge is managing power dissipation in the series-pass element of the linear amplifier while maintaining speed.

The real-time calculation is the other half of the system. As the pattern generator directs the beam deflection, it simultaneously runs a fast convolution of the written pattern with a pre-calibrated point-spread function (PSF). This calculation, performed in dedicated hardware like a field-programmable gate array (FPGA), predicts the cumulative dose at the current beam position from all nearby exposed points. It then generates a correction voltage signal proportional to the required energy adjustment to achieve uniform developed linewidth. This signal is sent to the modulation input of the high-voltage supply with minimal latency. The synchronization between beam position, dose calculation, and voltage modulation must be exact to within one pixel dwell time.

An alternative or complementary method involves modulating the beam current instead of voltage. This adjusts the dose rate directly. A similar high-bandwidth power supply is needed for the gun's Wehnelt or bias electrode to modulate the beam current with high linearity and speed. Often, a combined approach is used: coarse correction via pattern fracturing and dose assignment (software PEC), and fine, real-time correction via dynamic beam energy/current modulation. The power supply system must support both control inputs.

Validation of such a system is complex. It requires writing sophisticated test patterns and using a critical-dimension scanning electron microscope (CD-SEM) to measure linewidth uniformity improvements. The power supply's performance is quantified by its modulation bandwidth, small-signal step response, and the stability of its output during modulation (absence of ringing or noise induced by the switching activity). The integration of this dynamic high-voltage control directly addresses a fundamental physical limit in EBL, pushing the achievable resolution and pattern fidelity closer to the theoretical limit of the tool's optics, which is crucial for advanced photomask manufacturing and direct-write applications for niche devices.