High-Voltage Strategy for Crack Suppression in Electron Beam Melting and Solidification

Electron Beam Additive Manufacturing (EBAM) and Electron Beam Melting (EBM) are powder-bed fusion techniques used to fabricate high-value metallic components, particularly from refractory alloys like titanium and nickel-based superalloys. A focused, high-power electron beam selectively melts metal powder in a layer-by-layer fashion under high vacuum. A significant challenge in this process is the prevention of solidification cracks, also known as hot tearing, which occur due to thermal stresses and the formation of low-melting-point phases at grain boundaries during the final stages of solidification. The strategy for mitigating these cracks involves precise control over the thermal profile, and the electron beam's high-voltage power supply is a primary actuator for implementing this strategy.

The electron beam is generated by a thermionic or cathode emitter and accelerated by a high voltage, typically between 30 kV and 60 kV. The beam power, which is the product of the accelerating voltage and the beam current (P = V * I), determines the energy input into the powder. However, voltage and current are not equivalent in their effect on the melt pool. The accelerating voltage primarily determines the penetration depth of the electrons into the material due to the Bethe stopping power relationship. A higher voltage produces a more energetic beam that penetrates deeper, creating a taller, narrower, and deeper vapor cavity (keyhole) in the melt pool. A lower voltage results in more surface-limited, shallower heating.

Crack suppression strategies leverage this difference through dynamic high-voltage control during the beam's scan path. A common cracking mechanism occurs at the tail end of a melt track or at the borders of a contour scan, where heat extraction is rapid and the solidifying material is constrained by the surrounding cooler solid or powder. This creates tensile stresses that pull apart interdendritic liquid films.

One high-voltage strategy involves modulating the beam parameters to create a tailored thermal gradient. For instance, the primary melting of a vector might be performed with a standard high voltage and high current to ensure full fusion. As the beam approaches the end of the vector or a contour edge, the control system can command a rapid reduction in beam current while simultaneously increasing the accelerating voltage. This reduces the total power (reducing heat input to prevent overheating neighboring areas) but increases the penetration depth. The effect is to create a deeper but less intense hot zone that promotes a more favorable temperature gradient, encouraging directional solidification back towards the center of the melt pool rather than creating a sharp solidification front perpendicular to the scan direction.

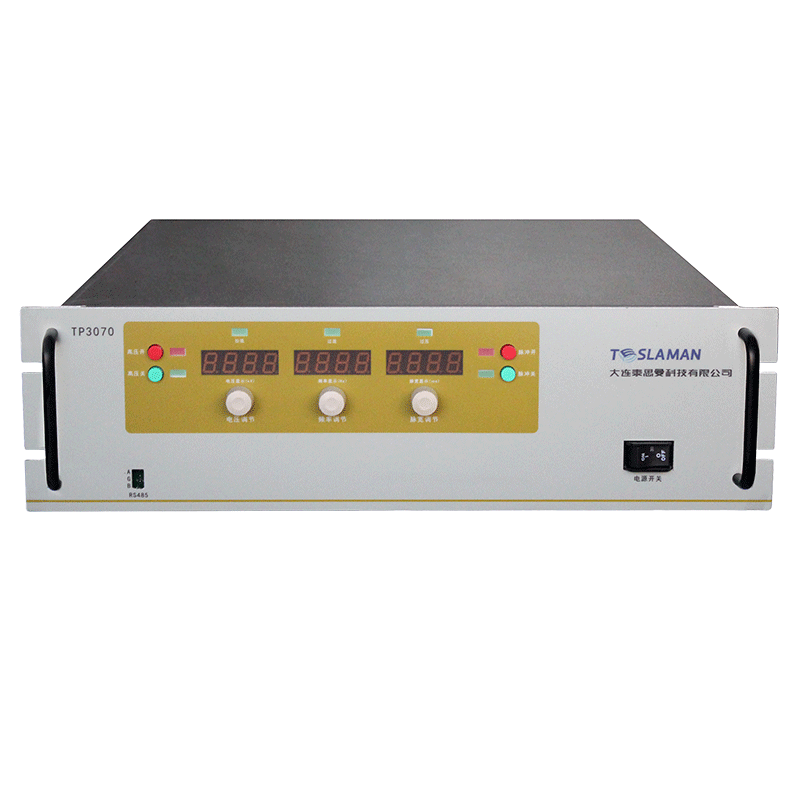

Another strategy is used for pre-heating or post-heating (often called defocusing). To reduce thermal gradients at the start and end of a melt track, the beam can be briefly defocused (by altering the lens currents) and operated at a lower voltage and current. This creates a broader, shallower heat source that gently raises the temperature of the surrounding powder bed, reducing the thermal shock when the focused melting beam arrives. Implementing this requires the high-voltage supply to respond quickly to commands to switch between different operating points that are part of a pre-programmed scan strategy for each layer.

Furthermore, for alloys particularly prone to cracking, a multi-pass strategy is employed. A first pass with a high-voltage, lower-current beam might be used to lightly sinter and pre-heat the powder. The second pass, with optimal melting parameters, then fuses it. A final contour pass with tailored low-power, possibly higher-voltage settings can remelt the edge to refine the microstructure and relieve stresses. The synchronization of the high-voltage power supply with the magnetic lens currents and the beam deflection signals is critical for executing these complex multi-parameter scans reliably over thousands of layers.

Therefore, the high-voltage control system in an EBAM machine is integral to thermal management. It is not a static source but a dynamic tool used to shape the energy deposition in space and time. By strategically varying the accelerating voltage in concert with beam current, focus, and speed, it is possible to engineer thermal conditions that promote a columnar or equiaxed grain structure, minimize residual stress, and most importantly, avoid the formation of solidification cracks. This level of control is what enables the reliable production of safety-critical, crack-free aerospace components using electron beam additive manufacturing.