Accelerator High Voltage Power Supply Gradient Descent Algorithm

Particle accelerators for research, medical, or industrial applications require extreme stability and precision in their beam energy, which is directly determined by the accelerating high-voltage potential. Traditional voltage regulation relies on proportional-integral-derivative (PID) control loops referencing internal setpoints. However, for achieving optimal beam characteristics—such as minimal energy spread, precise beam position, or specific interaction rates—a more sophisticated approach is sometimes necessary. The application of optimization algorithms, notably gradient descent techniques, to the real-time or supervisory control of high-voltage power supplies represents an advanced frontier in accelerator tuning and stabilization. This discussion explores the conceptual framework and practical implications of implementing gradient descent algorithms for high-voltage power supply control in accelerator systems.

The fundamental challenge is that the "optimal" operating point for an accelerator is often defined by an external, non-electrical metric that is a complex, non-linear function of many parameters, including the high voltage. For example, in a medical isotope production cyclotron, the optimal point might maximize the yield of a specific isotope, which depends on beam energy (voltage), beam current, target conditions, and other factors. In a beamline for spectroscopy, the goal might be to minimize the beam spot size on a sample, which is influenced by focusing elements whose settings are interdependent with the beam energy. Manually tuning the high voltage to find this optimum is time-consuming and suboptimal. A gradient descent algorithm automates this search.

The core principle involves defining a cost (or loss) function, **J**, that quantifies deviation from the desired outcome. In the isotope production example, **J** could be inversely proportional to the detected isotope yield. The high-voltage power supply setpoint, **V**, is one of the control variables. The gradient descent algorithm seeks to find the value of **V** that minimizes **J**. It does this iteratively by measuring the gradient of the cost function with respect to the voltage, ∇J/∇V, and then adjusting **V** in the opposite direction of this gradient. The update rule is: **V_new = V_old - α * (∇J/∇V)**, where **α** is the learning rate or step size.

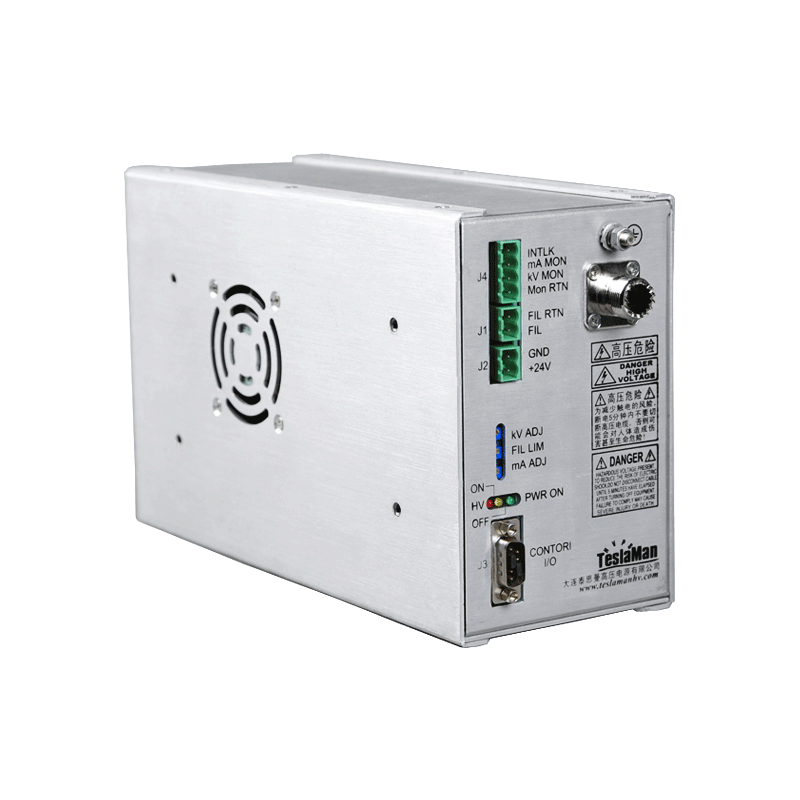

The critical implementation step is estimating the gradient. A straightforward method is the finite-difference approach. The control system slightly perturbs the high voltage by a small, precise amount δV (e.g., 10 V on a 100 kV supply). It then measures the resulting change in the cost function, δJ, by monitoring the relevant beam or target sensor (e.g., a gamma spectrometer for isotope yield). The gradient is approximated as δJ/δV. This perturbation and measurement must be performed in a time short enough that other system variables remain relatively constant, yet long enough for the beam and target response to settle. This imposes specific requirements on the high-voltage power supply: it must be capable of making extremely precise, small-magnitude setpoint changes (δV) with high reproducibility and low noise. The resolution of its digital-to-analog converter and the stability of its internal voltage reference become directly linked to the algorithm's ability to discern a meaningful gradient.

The learning rate **α** is a crucial parameter. If too large, the algorithm may overshoot the minimum, causing oscillations or instability in the beam. If too small, convergence to the optimum is slow, wasting valuable beam time. In practice, **α** may need to be adaptive. Furthermore, the cost function landscape is often multi-dimensional and may contain local minima. The algorithm might need strategies to escape these, such as simulated annealing or incorporating momentum terms, which remember the direction of previous updates.

Integration with the power supply's native control loop is paramount. The gradient descent algorithm typically operates as a supervisory or outer loop. It outputs a voltage setpoint, which is then passed to the supply's internal high-speed PID regulator. This internal regulator must be exceptionally well-tuned to respond accurately to these changing setpoints without introducing its own oscillations. Any lag or overshoot in the internal loop will corrupt the gradient measurement, as the measured beam response would not be solely due to the intended voltage change but also to the transient behavior of the supply itself. Therefore, the power supply's closed-loop bandwidth and damping characteristics are foundational to the success of the higher-level algorithm.

Real-world complications abound. The relationship between voltage and the cost function is often noisy due to statistical variations in beam interactions, sensor noise, or fluctuating vacuum conditions. The gradient estimation must therefore incorporate filtering or use multiple perturbation cycles to average out noise. The algorithm must also include safety constraints, ensuring the voltage never drifts outside a safe operating window for the accelerator structure or the power supply itself. This can be implemented as hard limits or by adding penalty terms to the cost function.

A significant application is in compensating for long-term drift. Accelerator high-voltage terminals can experience slow voltage drift due to temperature changes, conditioning effects, or aging components. A gradient descent algorithm can run continuously at a very slow pace, making tiny perturbations and adjustments to hold the cost function (e.g., beam position on a diagnostic screen) at a constant minimum, thereby actively compensating for drift without operator intervention. This transforms the power supply from a static voltage source into an adaptive beam optimization tool.

In conclusion, the implementation of gradient descent algorithms on accelerator high-voltage power supplies marks a shift towards intelligent, objective-driven control. It demands not only algorithmic sophistication but also superior hardware performance: micro-volt-level setpoint resolution, ultra-stable output, fast settling times, and seamless digital interfacing. By directly linking the high-voltage setpoint to the ultimate performance metric of the beam, this approach enables automatic optimization of complex accelerator processes, enhances stability against drift, and maximizes the efficiency and quality of outputs ranging from scientific data to medical radioisotopes, pushing the operational envelope of accelerator facilities.