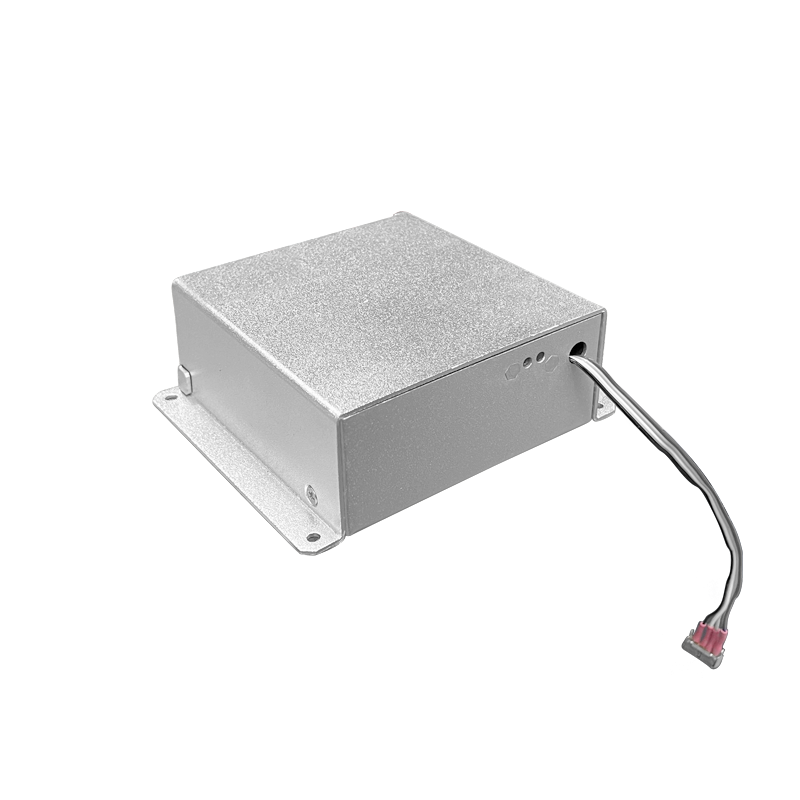

Mass Spectrometer Electron Impact Ion Source Power Supply

The electron impact (EI) ion source remains a cornerstone ionization technique in gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and other analytical mass spectrometry systems. Its operation hinges on the generation of a stable, controlled flux of electrons with precisely defined energy, which then interact with vaporized analyte molecules to produce characteristic fragment ions. The power supply system responsible for creating and regulating this electron beam is a critical, yet often under-appreciated, component whose performance directly dictates key analytical figures of merit: sensitivity, reproducibility, and spectral fidelity. This discussion examines the specific technical requirements and operational considerations for the high-voltage and emission control power supplies within a modern EI ion source.

At its core, the EI source requires two primary electrical functions: electron emission and acceleration. A filament, typically made of rhenium or tungsten, is heated resistively to thermionic emission temperatures. This requires a well-regulated, low-voltage, high-current filament supply. The stability of this supply is paramount. Fluctuations in filament current translate directly to variations in filament temperature, which in turn cause drift in electron emission current. Since the total ion current produced is proportional to the electron flux, such drift manifests as changing sensitivity during an analysis run, compromising quantitative accuracy. Therefore, the filament supply must provide exceptionally stable DC, often with current regulation better than 0.1%, and be designed to source this current through leads that may have significant inductance due to the physical layout within the vacuum chamber. Furthermore, the supply must incorporate soft-start circuitry to prevent inrush currents that could mechanically stress the fragile filament, and it should allow for precise, programmable control of the emission current setpoint.

The emitted electrons are then accelerated toward an anode, often called the trap or a set of focusing electrodes, by a fixed potential difference. This electron energy, typically standardized at 70 eV to enable library matching, is controlled by the acceleration voltage supply. The absolute accuracy and, more critically, the stability of this high voltage (usually in the range of 30 to 150 V, though relative to a different ground it can be in the kV range) are fundamental. A variation of even 0.5 eV can alter the ionization efficiency and, more importantly, the fragmentation pattern of molecules, changing the relative abundances of ions. This would render spectral libraries useless and make compound identification unreliable. Consequently, the acceleration voltage supply must be a precision reference, with ultra-low ripple (in the microvolt range) and excellent long-term drift characteristics. It is often derived from a highly stable, temperature-compensated reference and a low-noise amplifier, isolated from the noisy digital control sections of the instrument.

However, the true complexity arises from the interaction and isolation of these supplies within the ion source's floating potential. In a common configuration, the entire ion source block, including the filament, is held at a high positive potential (e.g., +1000 to +3000 V) relative to the mass analyzer's entrance. This is the "ion extraction" or "source potential." This means the filament supply, which provides, say, 5V at 2A to heat the filament, must float precisely at this high DC potential. Any coupling of AC noise from the filament driver into this high-voltage platform will directly modulate the effective electron energy. Therefore, the filament supply must be an isolated, "floating" design with exceptionally low primary-to-secondary capacitance and common-mode noise rejection. The transformers or isolated DC-DC converters used must be carefully shielded and often operate at high frequencies to minimize capacitive coupling. Ground loops and stray coupling paths must be meticulously managed in the mechanical design.

A third critical supply provides the bias for the repeller or draw-out electrode. This electrode, positioned behind the ionization volume, applies a small positive potential (tens of volts) to push the newly formed positive ions out of the source and into the mass analyzer. The stability and fine adjustability of this repeller voltage are crucial for optimizing ion transmission efficiency, which directly impacts instrument sensitivity. Its setting often requires empirical tuning for different source conditions or analyte types. Therefore, this supply, while lower in voltage, must also be a precision, low-noise, floating unit, capable of fine-resolution adjustment.

Modern EI sources also incorporate lens electrodes for focusing the electron beam and sometimes for controlling the spatial distribution of ions. These require additional, stable bias supplies. The interplay between all these voltages—filament potential, acceleration voltage, repeller voltage, and lens biases—defines the electron current density, the ionization volume, and the ion extraction field. Their collective stability ensures that the ion source operates at a consistent "tune," a prerequisite for obtaining reproducible mass spectra over time and across instruments.

The power supply system must also be robust. The EI source operates in a demanding environment: high vacuum, significant thermal cycling as the filament heats and cools, and exposure to a wide variety of chemical species, some of which can deposit insulating or conductive layers on electrodes. The supplies must be protected against arcs, which can occur if conductive deposits create short paths. Fast-acting current limiters and arc suppression circuits are essential to protect both the sensitive electronics and the fragile filament. Furthermore, the control interface must allow the instrument's main computer to precisely sequence the power-up and power-down of these supplies to ensure source longevity, perhaps ramping the filament current slowly while managing the high potentials to prevent spurious discharges during pump-down or venting cycles.

In summary, the power supply cluster for an EI ion source is a symphony of precision, isolation, and stability. It is not merely a collection of voltage and current sources but an integrated system where the noise performance and ground integrity of one supply directly affect the performance of another. Its design prioritizes microvolt-level stability, nanoamp-level noise, impeccable isolation to withstand kilovolt potentials, and ruggedness to survive the analytical environment. The consistency of the mass spectral data, the reliability of library searches, and the accuracy of quantitative results in countless GC-MS analyses are fundamentally dependent on the unseen performance of these specialized power supplies.