Electron Beam 3D Printing Real-Time Melt Pool Monitoring Power Supply

Additive manufacturing via electron beam melting (EBM) is a powerful technique for producing high-density, complex metal parts from titanium, nickel, and other alloys. The process occurs in a high vacuum, where a focused electron beam scans across a powder bed, inducing rapid melting and solidification. The stability and quality of the melt pool—the localized volume of molten material—are the primary determinants of part integrity, dictating factors like porosity, surface roughness, and residual stress. Real-time monitoring of this melt pool, typically through high-speed infrared pyrometry or co-axial optical imaging, is essential for closed-loop process control and defect detection. The power supplies for these monitoring systems, however, operate in one of the most electromagnetically hostile environments imaginable, and their design is critical to extracting a clean, meaningful signal from a background of intense interference.

The monitoring sensor, often a high-speed indium gallium arsenide (InGaAs) or mercury cadmium telluride (MCT) photodiode array, views the process through a viewport. It detects the intense near-infrared and infrared radiation emitted by the melt pool, which is at temperatures exceeding 2000°C. To achieve the necessary sensitivity and bandwidth (often requiring microsecond-scale exposure times to "freeze" the dynamic pool), these detectors require a stable, low-noise, high-voltage bias supply. The challenge is not in generating this bias voltage per se, but in preventing the massive amounts of electromagnetic interference (EMI) generated by the main electron beam gun from completely swamping the signal.

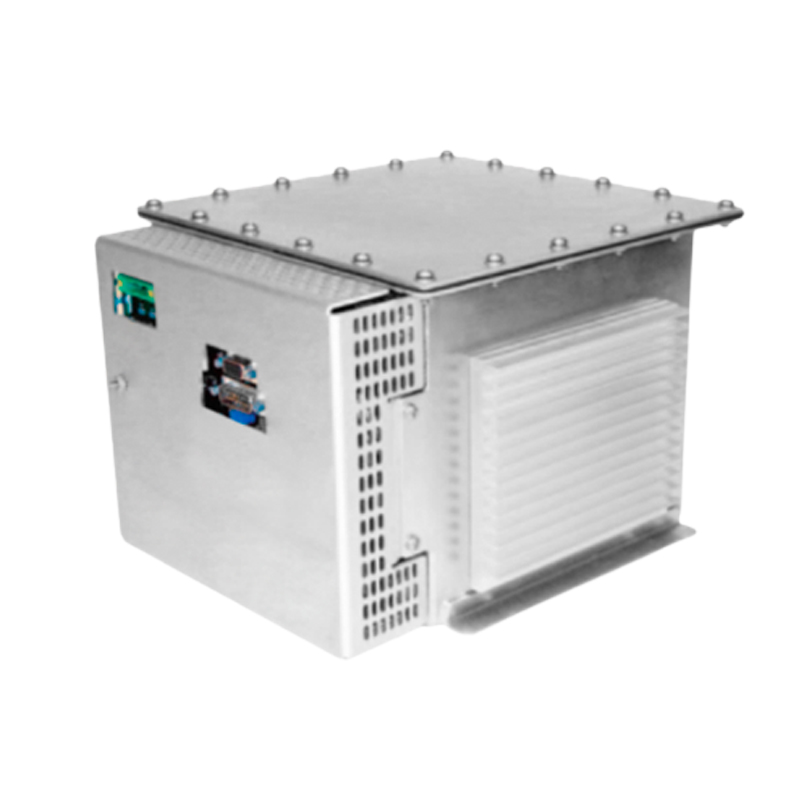

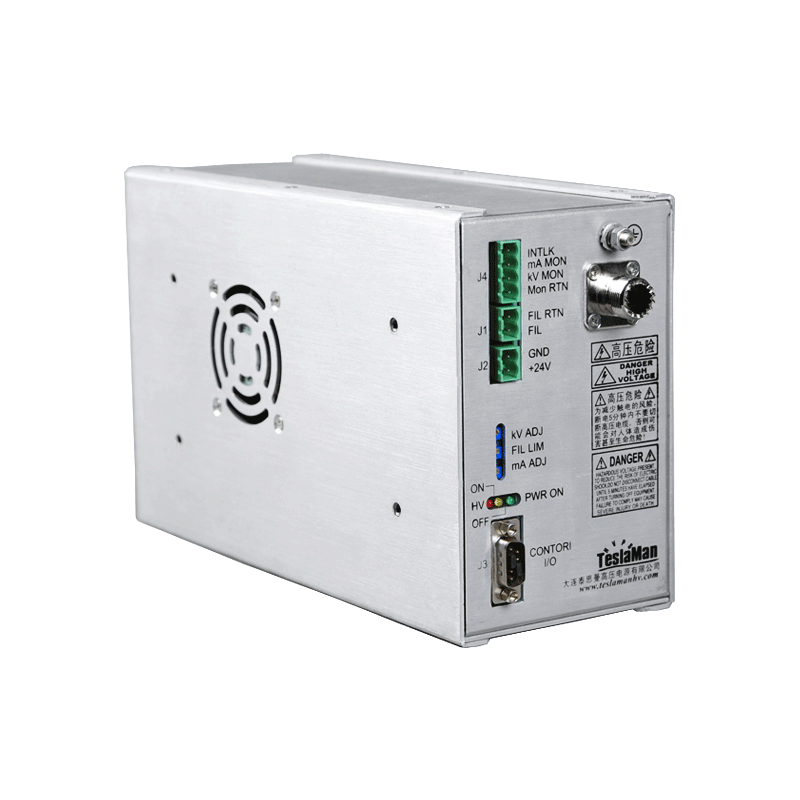

The primary beam gun operates at high voltages (typically 30-60 kV) and currents (up to tens of milliamps), with beam deflection coils switching at high frequencies (kHz to MHz range) to execute the scan path. This constitutes a potent source of both conducted and radiated EMI. The deflection amplifiers, in particular, are high-speed, high-current circuits that can induce significant ground plane noise. Any fluctuation in the local ground potential between the monitoring detector and its signal conditioning electronics will be interpreted as a signal. Therefore, the first principle for the monitoring power supply is absolute galvanic isolation. The detector and its immediate preamplifier are ideally housed in a shielded enclosure directly on the viewport flange. The bias voltage for the detector is generated locally within this enclosure by a dedicated, compact, and well-filtered DC-DC converter. The power for this converter is supplied via an isolated power feed—either through a dedicated isolation transformer with heavy shielding or via a battery pack within the enclosure for short-duration builds. This breaks any direct conductive path for ground loops.

The second principle is comprehensive shielding and filtering. The entire monitoring module must be enclosed in a continuous, conductive housing with RF gaskets on all seams. The viewport itself is often coated with a transparent conductive layer (like indium tin oxide) and connected to the shield to form a continuous Faraday cage. All input/output lines—power in, signal out, control lines—must pass through feedthrough filters that suppress both common-mode and differential-mode noise over a broad frequency spectrum, from the low-frequency harmonics of the beam current modulation to the high-frequency content of the deflection spikes. The bias supply's internal switching frequency, if it uses a switching regulator, must be carefully chosen and synchronized, if possible, to avoid intermodulation with the beam blanking or deflection frequencies.

Furthermore, the monitoring system often requires pulsed operation or high-speed gating. To enhance the signal-to-noise ratio, the detector might be synchronized with the electron beam scan, only acquiring data when the beam is illuminating a specific region of interest or using a short exposure time timed to the beam's dwell. This requires the bias supply or a downstream modulator to be able to gate the detector on and off with nanosecond precision based on an external trigger synchronized to the beam control computer. This synchronization itself must be done with fiber-optic or isolated digital links to prevent noise injection.

Finally, the power supply must be exceptionally robust and reliable. The environment near the build chamber involves significant thermal cycling, mechanical vibration from pumps and cooling systems, and potential contamination from metal vapors. The components must be selected for high-temperature operation, and the design must ensure that no single-point failure can lead to a high voltage being misapplied, which could damage the expensive detector array. In summary, the real-time melt pool monitoring power supply is a key enabler of process intelligence in electron beam 3D printing. Its success is measured by its ability to remain electromagnetically "silent" and stable while in close proximity to an intense, pulsed electron beam, thereby allowing the subtle infrared signature of the melt pool dynamics to be accurately captured and used for real-time quality assurance and control.