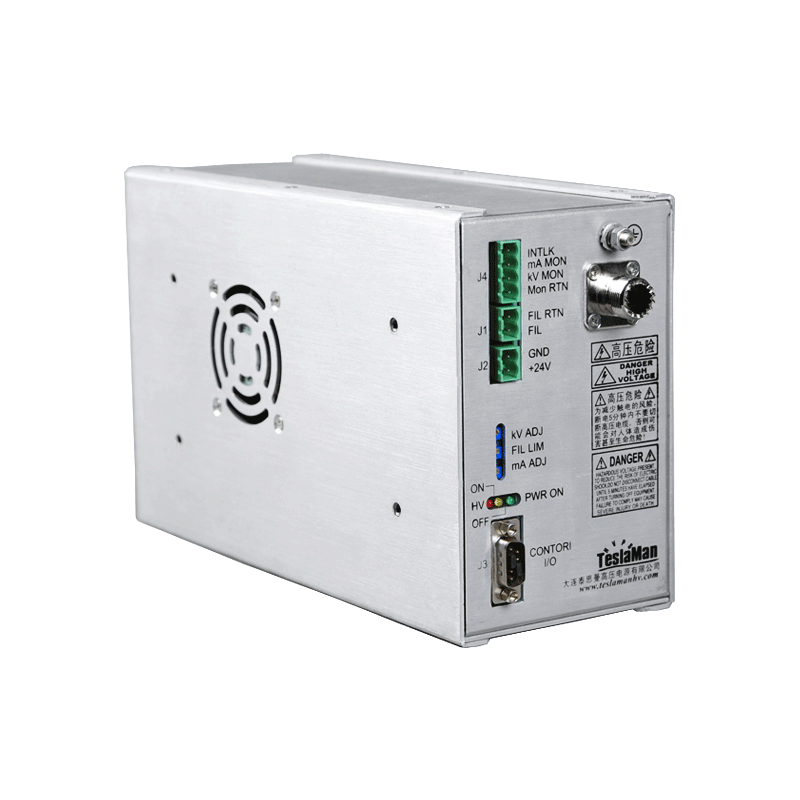

Mass Spectrometer Ion Trap Multidimensional RF High Voltage Power Supply

Ion trap mass analyzers, including three-dimensional quadrupole ion traps (Paul traps) and linear ion traps, are renowned for their high sensitivity, MS^n capabilities, and compactness. Their operation hinges on the application of a fundamental radio-frequency (RF) quadrupolar field to a set of electrodes to confine ions in space. For advanced analytical functions like mass-selective ejection, resonance ejection, and sophisticated ion manipulation (e.g., collision-induced dissociation, ion isolation, and charge detection), this fundamental RF field must be precisely modulated, supplemented with auxiliary waveforms, and often applied across multiple electrode sets. The "multidimensional" RF high-voltage power supply system is the electronic engine that generates and orchestrates these complex waveforms, defining the trap's mass range, resolution, scan speed, and functional versatility.

At its core, the system must generate a primary, high-amplitude, high-frequency sine wave. For a typical benchtop trap, this involves a frequency (Ω) in the range of 1-2 MHz and a zero-to-peak amplitude (V) that can be scanned from a few hundred to several thousand volts to bring ions of different mass-to-charge ratios (m/z) to the boundary of stability for ejection. The stability and spectral purity of this RF waveform are paramount. Any harmonic distortion or phase noise modulates the effective confining potential, leading to peak broadening, reduced resolution, and poor mass accuracy. Therefore, the RF amplifier and its resonant output network are designed for exceptional linearity and low noise. The amplitude must be controllable with high precision and linearity over its entire range, as the mass scale calibration depends directly on the relationship between m/z and the applied RF amplitude. This is often achieved using a linear RF power amplifier (e.g., class A or AB) driven by a direct digital synthesizer (DDS), or via a highly linear amplitude modulation scheme in a switching amplifier.

The "multidimensional" aspect arises from the need for additional, precisely timed waveforms on other electrodes. The most common is the supplementary alternating current (AC) waveform applied to the end-cap electrodes in a 3D trap or across opposing rods in a linear trap. This low-voltage (tens of volts), high-frequency (tens to hundreds of kHz) signal is used for resonant excitation. Its frequency corresponds to the secular frequency of a trapped ion, causing the ion's orbit to expand for either collision-induced dissociation (CID) or mass-selective ejection. The power supply system must generate this AC waveform with independent frequency and amplitude control, and it must be capable of injecting it onto the electrodes without coupling or interfering with the primary high-voltage RF. This requires sophisticated filtering and isolation networks. Furthermore, for advanced scan modes like resonance ejection, the frequency and/or amplitude of this AC waveform may need to be swept or stepped in a coordinated manner with the main RF scan.

Modern ion traps, especially those used for high-resolution charge detection or complex ion manipulations, may employ additional electrode sets with independent RF drives. For instance, a segmented linear ion trap might have different sections biased with different RF amplitudes to create axial potential wells for ion storage or mobility separation. This requires a multi-channel RF supply where the amplitude and phase of each channel can be independently programmed and synchronized. The phase relationship between RF channels is particularly critical; mismatched phases can create unintended dipolar or hexapolar field components that degrade trapping performance. The control system must manage these multi-channel outputs with nanosecond-level timing precision.

The integration of direct current (DC) potentials further adds to the dimensionality. Trapping, axial ejection, and lensing potentials are applied as DC offsets superimposed on the RF electrodes via bias-T networks. The power supply system must provide these stable, low-noise DC levels, and they must be adjusted in concert with the RF and AC waveforms during a scan function. All these supplies—the main RF, the auxiliary AC, the multi-channel RF, and the DC biases—are commanded by a central digital sequencer that executes the mass spectrometry experiment step-by-step. The sequencing demands are intense: a single analytical scan may involve ramping the main RF amplitude, simultaneously sweeping an auxiliary AC frequency, and pulsing a lens DC voltage, all within tens of milliseconds.

The design challenges are immense, encompassing high-frequency power electronics, thermal management of RF amplifiers, prevention of cross-talk and ground loops, and ensuring the absolute reliability of waveforms that have a direct, nonlinear impact on ion motion. A well-designed multidimensional RF supply transforms the ion trap from a simple mass filter into a programmable "ion reactor," capable of isolating a single ionic species from a complex mixture, fragmenting it in a controlled manner, and analyzing the products—all within the same physical device. The stability and programmability of these high-voltage RF waveforms are what enable the exquisite analytical depth and sensitivity that make ion traps indispensable in proteomics, metabolomics, and pharmaceutical analysis.