High-Voltage Synchronization for Multi-Jet Parallel Electron Beam Printing

The evolution of electron beam-based additive manufacturing and direct-write lithography is increasingly moving towards parallelization to overcome the throughput limitations inherent in single-beam systems. Multi-jet parallel printing, where multiple electron beams operate simultaneously to write patterns or fuse material, presents a formidable challenge in high-voltage engineering. The core of this challenge is not merely providing high voltage to several beams, but achieving precise electrical synchronization between them. This synchronization encompasses the accelerating voltage, beam blanking, and deflection signals, and is critical for ensuring pattern fidelity, dimensional accuracy, and process uniformity across the entire writing field.

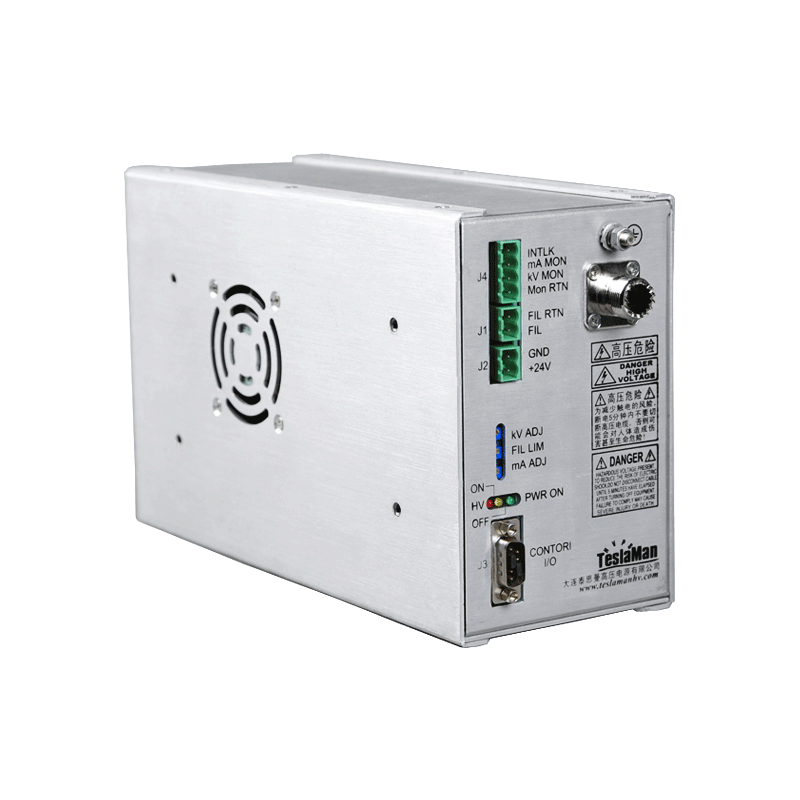

Each electron beam in a parallel array requires its own set of high-voltage and high-speed control signals. At the most basic level, each beam column requires a high-voltage power supply for the final acceleration stage, typically in the range of 1 to 30 kilovolts depending on the application. The primary requirement here is not just individual stability, but matching and tracking between supplies. If one beam's acceleration voltage drifts by even 0.05% relative to its neighbors, the resulting difference in electron landing energy can cause variations in developed feature size in resist or melt pool depth in additive manufacturing. Therefore, the high-voltage modules are often designed as master-slave or parallel-interleaved systems. A single ultra-stable master voltage reference is distributed to multiple regulated output stages, ensuring all accelerating voltages track each other with near-perfect correlation, rejecting common-mode noise and drift.

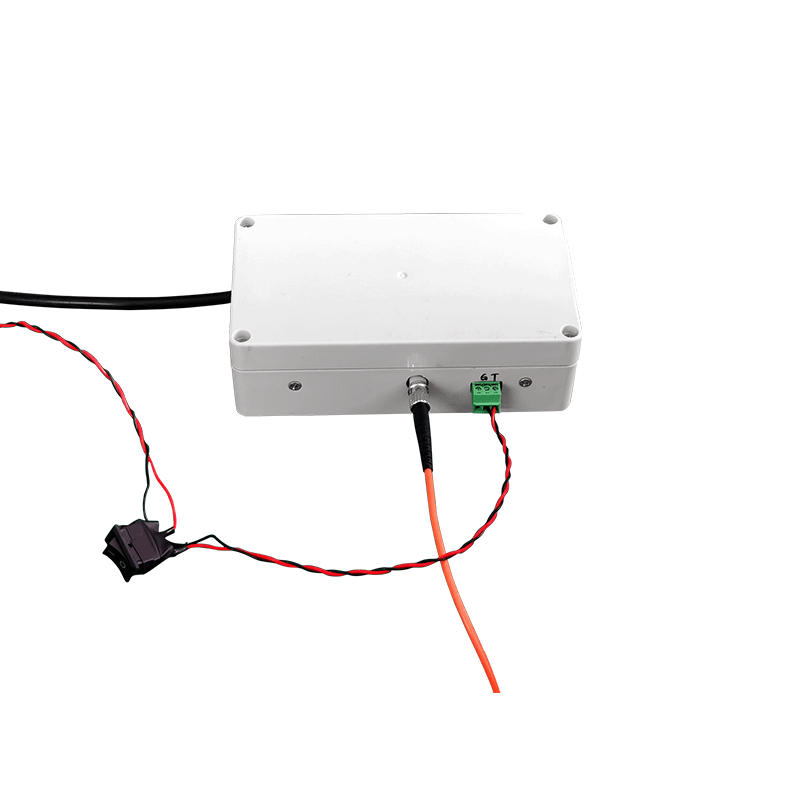

The complexity escalates significantly with beam blanking. To create a pattern, each beam must be independently switched on and off at nanosecond speeds. This is achieved by applying a high-speed blanking voltage, often several hundred volts, to a pair of deflection plates or an aperture in each column. The synchronization of these blanking signals is paramount. Temporal jitter between beams translates directly to placement errors on the substrate. A beam that fires a few nanoseconds late will deposit energy at a slightly different physical location if the stage or the other beams are moving. To mitigate this, a central timing generator, often phase-locked to a highly stable oscillator, distributes triggering signals to each blanking amplifier via matched-length transmission lines to ensure equal signal propagation delays. The blanking amplifiers themselves must have identical rise and fall times to prevent one beam from having a longer effective exposure time.

Furthermore, the deflection systems for each beam must be synchronized if they are to write a coordinated pattern. In some architectures, each beam has its own miniature electrostatic or magnetic deflection system. The analog voltages or currents driving these deflectors must be precisely coordinated. This requires a multi-channel, high-speed digital-to-analog converter system where all channels are updated simultaneously from a shared memory buffer, driven by the same clock. Any skew between channel updates will cause the beams to be momentarily misaligned relative to the intended pattern. The power supplies for these deflection amplifiers must also be exceptionally low-noise, as noise on the deflection signals appears as high-frequency positional jitter of the beam spot, blurring fine features.

Grounding and electromagnetic compatibility become monumental tasks in such a system. The simultaneous switching of high-voltage blanking signals in multiple channels generates substantial high-frequency noise. Without meticulous design, this noise can couple into sensitive analog circuits, such as the beam current sensors or the deflection DAC references, causing crosstalk between beams. This is managed through comprehensive shielding, the use of differential signaling for control lines, segmented ground planes, and often, optical isolation for critical timing and control signals to break ground loops.

Thermal management is another synchronization-adjacent concern. The heat dissipated by the high-voltage and high-speed switching components in each channel must be uniform. A channel running hotter than others may experience thermally induced drift in its blanking delay or deflection gain. Therefore, cooling systems are designed for uniform airflow or liquid cooling plate temperatures across all modules.

In practice, the high-voltage synchronization system is the unseen conductor of a multi-beam orchestra. Its performance determines whether ten or a hundred beams act as a single, coherent tool or as a collection of independent, misaligned instruments. Successful implementation enables dramatic gains in writing speed for maskless lithography, or in build rate for additive manufacturing, without sacrificing the precision and resolution that make electron beam techniques valuable. It transforms parallel e-beam technology from a laboratory curiosity into a viable high-throughput production method for advanced semiconductors, nano-devices, and customized micro-components.